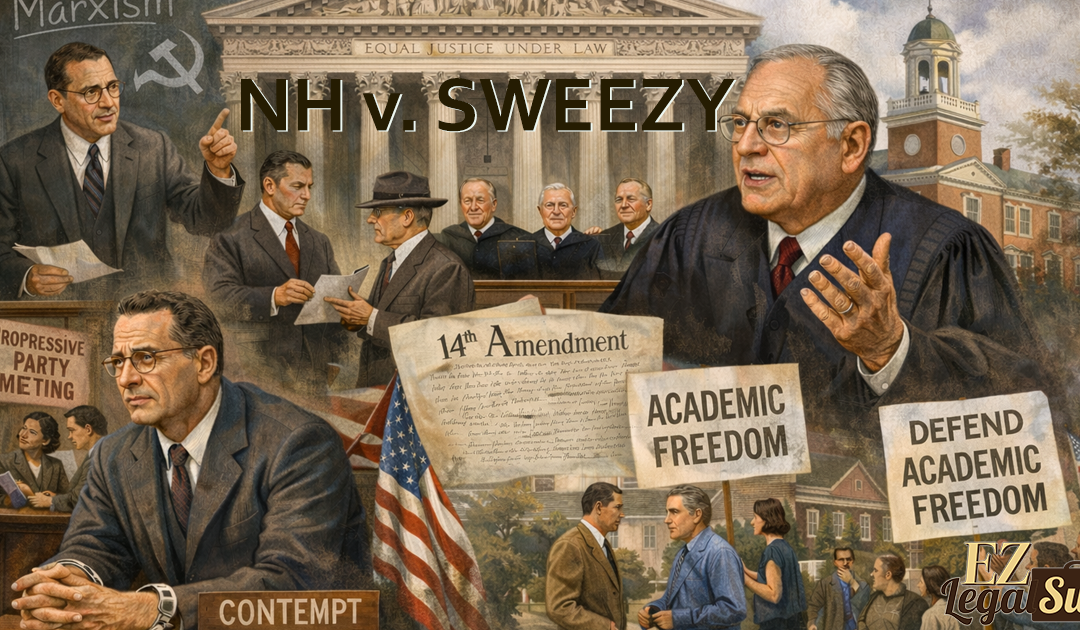

Summary of Sweezy v. New Hampshire (354 U.S. 234, 1957)Background and Context

During the Cold War era of anti-communist investigations (McCarthyism), the New Hampshire legislature enacted the Subversive Activities Act of 1951, which defined “subversive persons” and barred them from state employment. In 1953, it was amended to authorize the state Attorney General, Louis C. Wyman, to act as a one-man legislative committee to investigate subversive activities, with broad powers to subpoena witnesses and hold hearings (public or private).Paul M. Sweezy, a Marxist economist, founding editor of Monthly Review, and occasional guest lecturer at the University of New Hampshire (UNH), became a target due to his leftist views.Proceedings Timeline

- January 1954: Sweezy was subpoenaed and questioned about his political beliefs, associations with socialists/communists, and involvement in the Progressive Party. He answered many questions (denying membership in the Communist Party and advocacy of violent overthrow) but refused others on First Amendment grounds.

- March 22, 1954: Sweezy delivered a guest lecture at UNH on Marxism/socialism.

- June 1954: Sweezy was subpoenaed again specifically about the content of his UNH lecture (e.g., whether he said socialism was inevitable in America) and further details on the Progressive Party. He refused to answer, citing lack of pertinence and First Amendment protections.

- Post-hearings: Attorney General Wyman petitioned the Merrimack County Superior Court to compel answers and hold Sweezy in contempt for refusal. The court did so on June 30, 1954; Sweezy was freed on bond pending appeal.

- New Hampshire Supreme Court: Upheld the contempt conviction, acknowledging infringement on Sweezy’s rights to free speech, association, and academic freedom but ruling it justified by the state’s interest in self-preservation against potential violent overthrow of government.

- U.S. Supreme Court:

- Argued March 5, 1957.

- Decided June 17, 1957 (companion case to Watkins v. United States).

- Reversed the conviction (6-2).

Key Issues and Refused Questions

Sweezy refused to answer:

- Details about his UNH lecture (e.g., “Didn’t you tell the class that Socialism was inevitable in this country?”).

- Questions about others’ involvement in the Progressive Party (e.g., associations of his wife or specific individuals with communists).

U.S. Supreme Court Holding and Reasoning

No single majority opinion, but reversed on constitutional grounds:

- Plurality Opinion (Chief Justice Warren, joined by Black, Douglas, Brennan): The investigation violated due process under the Fourteenth Amendment. The Attorney General’s mandate was overly broad and vague (“sweeping and uncertain”), lacking clear legislative direction on what information was sought or why these specific questions were pertinent. The state failed to show a compelling interest justifying infringement on liberties.

- Concurring Opinion (Justice Frankfurter, joined by Harlan): Focused on First Amendment violations, emphasizing academic freedom and political expression/association. Frankfurter’s concurrence famously stated: “It is the business of teachers and students to inquire, to study and to evaluate… otherwise our civilization will stagnate and die.” The inquiry improperly intruded on protected academic and political autonomy without sufficient justification.

- Dissent (Justices Clark and Burton): Would have upheld, arguing the state’s interest in investigating subversion outweighed individual rights here.

Outcome and Impact

Sweezy’s contempt conviction was overturned. The Court denied New Hampshire’s rehearing petition shortly after. The case is a landmark for protecting academic freedom and limiting government inquiries into political beliefs/associations, reinforcing that such investigations must be narrowly tailored and justified. It highlighted due process limits on legislative probes during the Red Scare era. The New Hampshire Act remained until repealed in 1973